Below you will find a list of questions by a range of stakeholders. This list will continue to be populated as the project progresses.

Questions have been grouped according to the topic or module.

How are you evaluating the AdaptNRM project?

As part of the NRM Fund program of research, AdaptNRM has a significant focus on monitoring and evaluation as part of the project. The federal government is also monitoring the program as a whole. In AdaptNRM, we primarily monitor engagement with the project, by NRM groups as well as other stakeholders, in order to gauge the level of interest in what we do as well as the resources we deliver. We do this by recording how many people attend our various meetings and discussions, the extent of conversation, and the nature of follow-up after a specific event.

Perhaps the most important aspect of our M&E is evaluating the process by which we engage with NRM groups and other stakeholders. Here we monitor and evaluate how we as a team engage with others, as well as how others engage with us. We do this by reflecting on our activities, as well as directly asking for feedback. It’s why we always ask NRM stakeholders to let us know what is their preferred method of communication and engagement, and when the best time is to hold an event. It’s also why we always ask whether or not NRM stakeholders feel that their input has been incorporated into the development of our resources. This is all part of our intent to continuously improve both the products we develop as well as our process of engagement.

So, please fill out our short surveys when we ask for feedback, and don’t hesitate to let us know how we’re travelling at any time – your feedback is most welcome.

Have we forgotten about mitigation?

Mitigation of GHG emissions is a topic that we are not directly covering in AdaptNRM, though the degree to which adaptation will be necessary depends on how much mitigation occurs at a global level. However, AdaptNRM’s philosophy is that any approach to adaptation planning should take into account that no maladaptive strategies are taken forward. Jon Barnett and Saffron O’Neil (2009) talked about maladaptation in an editorial in the journal Global Environmental Change, defining it as: “action taken ostensibly to avoid or reduce vulnerability to climate change that impacts adversely on, or increases the vulnerability of other systems, sectors or social groups.” (page 211). Maladaptation includes any action that increases greenhouse gases.

The adaptation planning framework we provide in The NRM Checklist strongly supports monitoring and evaluation, as well as reflection, in the planning process, thus enabling planners to identify any strategies that could potentially be maladaptive. Similarly, the assessment stage of the planning process should enable planners to identify if current practices either have win-win benefits for mitigation and adaptation, or otherwise.

As such, while we are not explicitly addressing mitigation of GHG emissions in our resources, our overall approach is founded on addressing it.

Mitigation can offer opportunities to NRM groups. Planting trees can mitigate carbon concentrations. By undertaking activities that can be mitigative and adaptive such as replanting riparian vegetation, you can achieve multiple benefits.

A useful report to read is: Lukasiewicz, A, Finlayson, CM & Pittock, J 2013, Identifying low risk climate change adaptation in catchment management while avoiding unintended consequences, National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility, Gold Coast, 95 pp.

Can we ask questions after we’ve had a chance to play with a module?

Absolutely. AdaptNRM is a ‘live’ project and ongoing feedback and questions are sought throughout its life (till June 2016). We understand that the timing of the release of our resources may not coincide with each NRM group’s needs, and as such we expect that while some would immediately use a resource as soon as it is released, others might take time. You can direct your questions to any AdaptNRM engagement team member – Lilly Lim-Camacho, Barton Loechel, Talia Jeanneret and Veronica Doerr – and we will try and assist as best we can.

How long will the AdaptNRM website be available for?

The AdaptNRM website, at this stage, is available indefinitely. While the project itself runs until June 2016, the website can stay ‘live’ for a very long time. Ability to update contents however may be restricted pending resourcing. There are possibilities of using this as a platform for other related resources, depending on interest and availability of resources.

How do I download data from the CSIRO Data Access Portal?

You can download a large range of map posters and datasets introduced in AdaptNRM. Weeds and Climate Change, Implications of Climate Change on Biodiversity and Helping Biodiversity Adapt all come with additional material you can download from the CSIRO Data Access Portal (DAP). Details of the maps and datasets available are provided in each topic’s technical guide.

Follow the links below for instructions on data access:

What have community champions done in the past?

Community champions can help drive change in organisations. They can show leadership, put pressure on organisations to act, be willing participants in planning activities and can provide opportunities to undertake climate adaptation activities. They can also trial options suggested in plans and can be early adopters of new practice. NCCARF has compiled resources for others to see what climate champions have done in their adaptation journey. Many initiatives are in place at NRM/CMA, local government and enterprise level, and some of them are captured in NCCARF website.

You can view ‘Adaptation Action Stories’ at http://www.nccarf.edu.au/content/adaptation-action-stories. Here you can find examples of adaptation policy making, adaptive management with traditional owners, responses to sea level rise and floods, and even relocation efforts at local government scale.

There are a number of case studies of good adaptation practice available as short easily accessible reports, some videos and some short examples from around Australia, on http://www.nccarf.edu.au/localgov/..

Climate Adaptation Champions at http://www.nccarf.edu.au/engagement/nccarf-climate-adaptation-champions describes NCCARF’s award recipients for the past four years. Here you find examples of efforts at individual, business, government and community levels.

The Climate Kelpie Managing Climate Variability Climate Champion program also provides information on Australian farmers taking part. Visit http://www.climatekelpie.com.au/farmers-managing-risk/climate-champion-program where you can read more on how each farmer is working with climate.

How can we engage community when they don’t believe in climate change? How do we get acceptance amongst sceptics?

CSIRO’s ongoing surveys of public attitudes toward climate change shows that the majority of people believe climate change is happening – most sceptics are simply unsure if some cause of the change might be natural climate cycles (see https://blogs.csiro.au/climate-response/videos/fourth-annual-survey-of-australian-attitudes-towards-climate-change/ for a quick video describing the latest survey results). Thus, NRM representatives may choose to start conversations based on no-regrets “adaptation”. In adapting to change, the cause becomes less important. Thus, adapting to a changing or variable climate or even just to an uncertain future, involves considering climate as only one driver of what the future might be like. Traditionally, this hasn’t been done and there are still few materials to assist with community discussions of adaptation per se. But the resources on future visioning could be applied in this general way, considering multiple drivers of change, thus reducing the focus on climate.

It may also be helpful to frame the issue differently depending on who you are engaging with. Recent work in consumer perspectives of climate adaptation (link to be made available) talks about different types of ‘personalities’ based on climate belief and climate adaptation action. In this research, it was found that the different consumer segments also have different priorities in life, implying that there are different levers to use when communicating with them – regardless of the topic. The sceptics in this research for example, prioritise ‘cost of living’, ‘health’ and ‘maintaining our way of life’. As such, in the instance of food purchasing and consumption that this research is based on, it could be assumed that approaching climate adaptation from these priorities would enable conversations to be had with a sceptic group.

The same principles can be applied with NRM stakeholders. It may be useful to understand what their key priorities are, and approach climate adaptation conversations from these priorities. Based on our experience, it would also be useful to have a suite of tools handy for difficult to avoid topics, such as uncertainty. You could use our uncertainty resource (Box 2, page 5 of the Adaptation Checklist) as a guide to demonstrate that it can be managed as long as its true implications are understood. Likewise, ensure that any communication you have with your stakeholders is simple, easy to understand and focused on issues that they can address. See an example of work done for the tourism industry.

Finally, there is significant literature that belief in climate change is rooted in an individual’s worldview, much in the same way as politics and religion (see Kahan, 2010 http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v463/n7279/full/463296a.html). This makes it a very difficult discussion to have, especially in the case of organisations and individuals who work with a wide range of stakeholders. Thus, in addition to the above ideas, make sure you focus on working with the champions you have rather than spending your energy and resources convincing the minority of true sceptics.

One thing that can be done is to try and move the discussion away fro being a belief system to one of logic. Scientists do not believe in climate change. They review the data and information that has been presented and ask many questions about rigour and analysis and based on the weight of the evidence will come to terms with what is happening. Its about risk – if 98% of flight engineers say that an aeroplane should be grounded, would you fly on it?

How do we capture decision-making that has already occurred?

The intent of the framework outlined in The NRM Adaptation Checklist is to be flexible. In most cases, aspects of climate-adapted planning will be picked up in different parts of the planning cycle at different times. Using the text on risks in the Checklist, you could quickly reflect on the risks of having been less climate-adapted in previous decisions. This may help you understand where previous decisions may need some urgent adjustment versus where they may not have been ideal but present little immediate risk to your plans.

If there are previous decisions that cannot be adjusted, you might use the information on risk to think about how else to mitigate the risks created by those previous decisions. These fixed decisions and their consequences can also be captured in the future visions for your region (as aspects you don’t have immediate control over), so that planning can occur with the consequences of those decisions in mind.

In considering risks associated with decisions that have been made you might want to think about questions such as:

- What are the short (couple of years), medium (10-20 years) and long term outcomes (more than 20 years that are likely to occur as a result of the decision?

- Is there a risk that the decision will have a negative impact on your adaptation plans?

- Will your decisions achieve their desired outcomes because of the impact of climate change?

How does the insurance industry do risk assessment and how can we bring that into the planning process?

The way the insurance industry has looked into risk assessments has changed, largely because weather events no longer follow historical boundaries. (See http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/how-the-insurance-industry-is-dealing-with-climate-change-52218/?no-ist) As such, the industry has changed to include climate modelling as a contributor to its risk assessments (see IAG presentation) in order to simulate extreme events, but this is not an easy task.

One of the key differences is that they consider not only the risk of things like extreme events happening and leading to negative consequences, they also consider the risk to their own organisations of making different decisions to handle that risk. This is what we refer to when we talk about risk-based approaches to decision-making. You can read this brief introduction to different decision-making approaches http://www.mediation-project.eu/platform/pbs/pdf/Briefing-Note-1-LR.pdf and reflect on the risks your organisation might take on by using particular approaches.

Other resources to explore:

- http://www.nccarf.edu.au/publications/climate-change-adaptation-industry-business

- http://www.igcc.org.au/Resources/Documents/property_assessing_climate_change_risks_for_investors.pdf

How dependent are adaptation plans on particular climate scenarios?

Your adaptation plans should be dependent on climate scenarios. That is how you can assess risk and work through the most appropriate options for the short, medium and long term. The ones you select should be realistic for your region and the time frames you are managing for. If you follow our guidance, you will be considering risk, but not implementing anything extreme (is based on long-term high emission scenarios) in the short term. You will be taking decisions that are robust to a range of climate scenarios, or which can be built on if the need arises (pathways approach). You need to be careful about implementing actions that are only good for short term outcomes and then may become a liability if longer term scenarios eventuate.

Will these planning guides need to change with new climate scenarios, such as issued by the recent IPCC 5th assessment report?

No, the planning guides show you how to deal with climate scenarios that may change over time as more information becomes available. We deliberately tried to make the guide robust to new information, as scenarios will definitely change over time as better information becomes available and models become better at projecting climate change at smaller scales than at present. Using new information is essential to keep your plans up to date, but the guidance on how to approach it or assess your approach should not change.

New examples will definitely become available over time, and these will be made available or can be sought after.

Have you considered the implications of native species becoming invasive and potentially weeds, as they move out of their current range?

Yes. It is almost inevitable that as the climate changes, the geographic distribution of many native species will change, in some cases resulting in ‘invasions’ into other ecosystems, creating new and different ‘novel ecosystems’. Some of these shifts in geographic distributions may be detrimental to pre-existing ecosystems, competing with incumbent native populations for resources (soil moisture, nutrients, sunlight etc). Measures to improve the adaptive capacity of some native species, such as establishment of vegetation corridors, may facilitate these invasions. Careful analysis and broad ranging consultation with multiple stakeholders may be required to determine if the invasive native should be classified as a weed and removed, or accepted as merely a native species adapting to climate change. These issues are discussed in Sections 5 and 6 of the Technical Guide.

To what extent has the Weeds and Climate Change module been integrated with the approach taken in the Adaptation Planning module?

The Weeds and Climate Change module has been developed to be used as a stand-alone resource, so that it is still fully functional without it being necessary to have read Module 1. Nevertheless, the modules are complimentary in that Module 1 provides a broad set of considerations around adaptation planning that can usefully inform the more specific issue of adaptation planning for weeds. Both modules adopt an adaptive management framework for climate change adaptation planning and implementation. In the case of the Weeds module, this framework is applied to the development of a weed management plan in section 10 of the Technical Guide. Both modules also provide a series of questions throughout to prompt thinking about the practical application of the ideas presented in the main body of text. Finally, both provide an extensive range of additional resources, including case studies and linked examples, that are integrated throughout the relevant sections of the document.

How regularly will the Data Access Portal be updated with new weed species and/or new and improved models?

Provision of the CLIMEX weed models has been enabled through the National Project funding. Over time new and updated information will no doubt become available, so at some time in the future a systematic review and update of the models may be advisable. However, this is likely to require additional resources and will depend upon funding availability at the time.

How do I find a list of the main weeds likely to be a risk to my region under future climate change using the Data Access Portal?

The DAP provides a range of supporting materials and information on weeds and climate change. This includes Australian and global maps of modelled species projections for current and 2070 climates for about 100 invasive plant species for which there are published CLIMEX models of relevance to Australia. As part of this collection, a list of key future weeds by region is provided in the ‘Related Materials’ link of the data collection titled “All CLIMEX models – AdaptNRM module 2: Invasive plant species and climate change”. Below are step-by-step instructions to locate this resource in the DAP:

1. Access the DAP at the following url: https://data.csiro.au/dap/home

The link to the DAP is also available both in the Technical Guide (Box 1 or Section 13.1 ‘Supporting materials and data’) and via the Weeds and Climate Change webpage www.adaptnrm.org

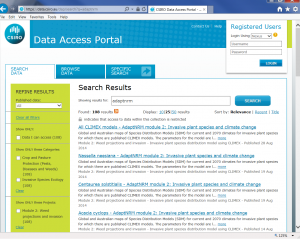

2. To locate the data collection titled “All CLIMEX models – AdaptNRM module 2 “Invasive plant species and climate change” enter “adaptnrm” into the search field of the DAP. This search term will also take you to a list of each of the individual weed models which have been entered under the weed species name.

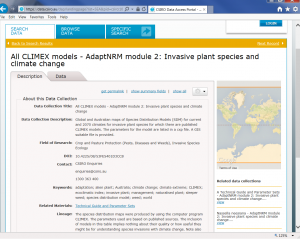

3. Click on the link “All CLIMEX models – AdaptNRM module 2: Invasive plant species and climate change”. This will take you to the data collection which includes two main Tabs: Description (of the data collection) and Data (which provides the complete list of downloadable weeds species distribution models).

4. Within the Description field you will see a sub-section titled Related Materials with a link to Technical Guide and Parameter Sets – click on this link. This will take you to a sub-collection of supporting information for the CLIMEX models:

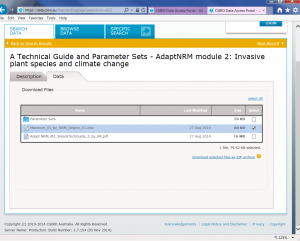

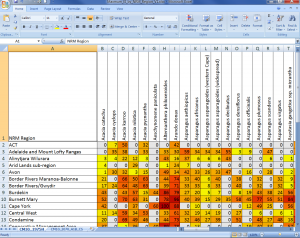

5. Click on the Data tab, which will then display an Excel file titled “Maxmum_EI_by_NRM_ Region_V1″. Select this file and then click on “download selected files as ZIP archive” to access the list of weeds by NRM regions for current and 2070 climates.

6. The Excel file displays the Ecoclimatic Index (EI), which is an overall indication of the modelled climatic suitability for a particular plant (columns) in a particular area (rows). The EI is shown for both under the current climate (baseline 1975) and for 2070. These measures of suitability are also colour coded, becoming a deeper red with higher modelled suitability (and, therefore, of greater concern to that particular region).

Given monitoring is such an important weed management action under climate change, what is the ideal technique and scale for monitoring weeds?

To provide information that can be compared against historical data and in order to generate trend data, the techniques and scale used should be comparable to those used in the past. A 10m x 10m plot size is common, although different regions and States have followed different conventions in the past. The approach may also depend on the nature of the problem and the means to address it (e.g. geographic scale of the area being managed, topography, type of weed, resources available for monitoring, etc.).